Digging into Dollar Dominance

What it is, what could happen, and a little bit of history

Enough dancing around – what is dollar dominance, and why does Steven Miran want to chip away it? And have we ever been close to this before? This week’s newsletter is going to dig into what dollar dominance means, how monetary policy can play a role in sustaining it, and what its elimination could mean for the US. There will be some callbacks to the post about exorbitant privilege, and also to different posts about trade and monetary policy writ large. Once again, I’m here to walk you through anything too technical. Here goes!

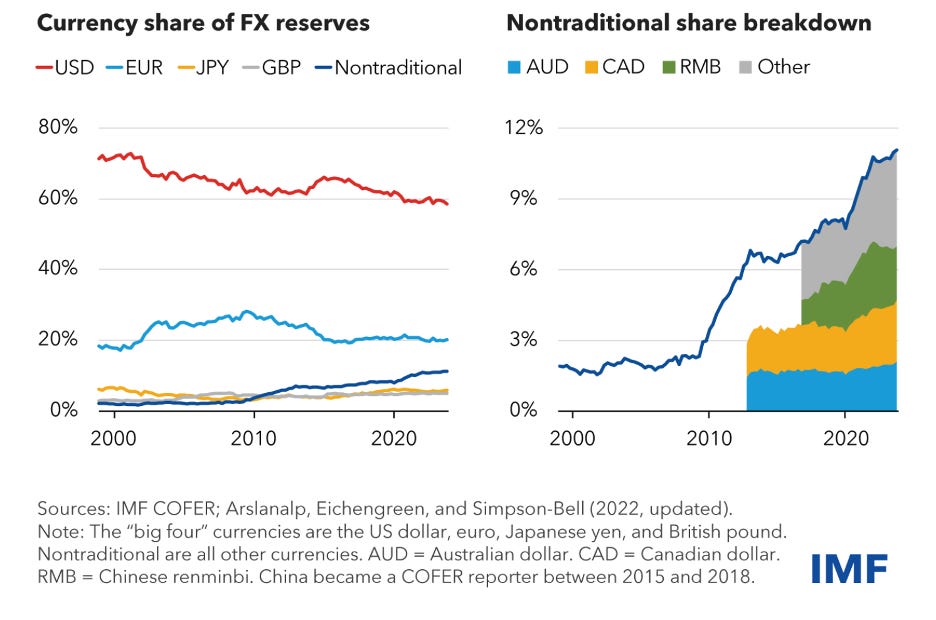

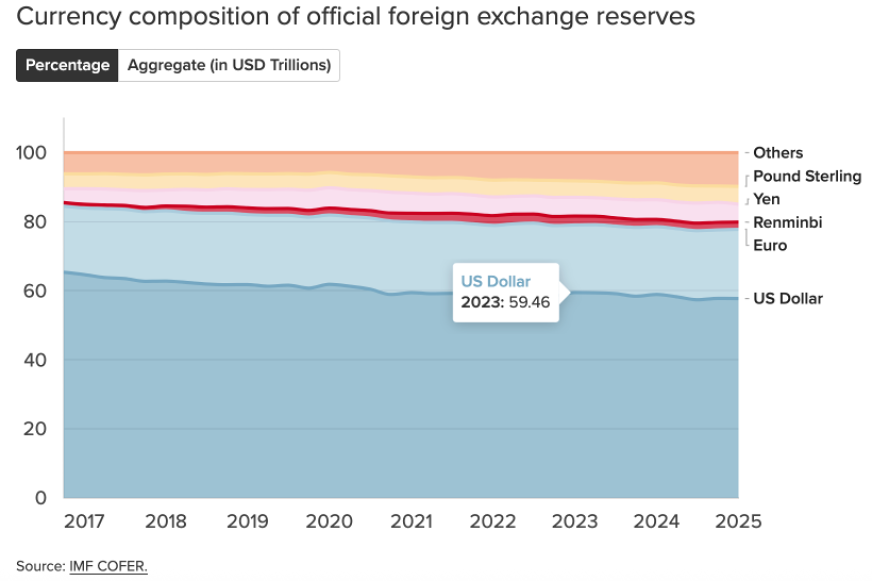

Dollar dominance refers to the fact that the US dollar is widely held, and in wide demand around the world for a variety of reasons. Part of that is trade – to buy goods and services from a given economy, the trade partner will at some point need access to the currency in which those exports’ prices are denominated. As of 2024, the US was the second largest global exporter of goods, and the largest exporter of services, so from a mechanical standpoint, there is likely to be considerable international demand for US dollars. The US dollar is also majority currency share of global foreign currency reserves, though that edge has been gradually decreasing over recent years (something I’ll talk about below).

As of July 2025, the US dollar still accounted for 58% of global foreign currency reserves (central bank holdings of foreign currencies around the world), with the next most dominant global currency being the Euro (close to 20%), followed by the British Pound Sterling and the Yen (both 5%), and the Renminbi (2%). This website from the Atlantic Council has a fun (nerdy) graphic showing the relative share of these currencies among foreign currency reserve holding, share of export invoicing (“the share of exports invoiced in a given currency,”) and the share of foreign exchange transactions (“the share of all currency trades of which a given currency was on at least one side of”), and you can see just how widely traded the US dollar is compared to other global currencies, for better or worse. Petroleum prices, even if sold by non-US economies, are typically denominated in US dollars; so are other commodities, including agricultural products, natural gas, and metals. Some economies adopt the US dollar as their national currency, which can create monetary complications down the line, if the dollar appreciates in global currency markets.

When economists and political economists talk about dollar dominance, they are usually referring to the exorbitant privilege that the US holds, for a host of structural and historical reasons. In a really quick summary, the Bretton Woods Accord established a fixed but adjustable exchange rate system pegged to the US dollar, which could be converted to gold at the fixed rate of $35 per ounce. This setup gave members “both exchange rate stability and the independence for their monetary authorities to maintain full employment (Bordo, 2017).” This arrangement increased global demand for the US dollar, which was in turn used increasingly as an international currency, and encouraged global purchases of the US dollar. The Bretton Woods arrangement broke down between 1968 and 1971, when inflation increased in the US and President Nixon ultimately suspended gold convertibility in 1971, and participants abandoned the pegged exchange rate system in 1973. Despite the end of Bretton Woods, international demand for the US dollar has remained high; there were few global competitors for that status, since by that point, central banks around the world had acquired reserves of US dollars. Because many international debts continue to be denominated in US dollars, global demand for US dollars remains high, pushing up the price of the US dollar, and dollar denominated assets like US Treasuries.

Dollar dominance is great for the US, insofar as it maintains demand for the US dollar, and insures against exchange rate volatility for the US. A domestic spillover effect of dollar dominance is high global demand for US government debt, leading to higher prices for US government bonds, and lower interest rates for those bonds (which move inversely to bond prices). Together, this gives greater fiscal space for the US government, or the ability to increase government deficits and debts without incurring larger sovereign debt costs, than for other economies around the world. However, it tends to hurt actors and institutions, namely exporting industries, that would benefit from a weaker US dollar. International spillovers also result from dollar dominance. If the US dollar appreciates in global currency markets, potentially because of interest rate hikes or other exogenous shocks, it makes dollar denominated debts more expensive for other countries, and increases the risk of sovereign default, or other economic crises.

In more recent years, the fact that many international obligations are denominated in US dollars contributes to sustained demand for the US dollar. This works like a self-fulfilling prophecy: the need to hold dollars for future obligations motivates the purchase of currency reserves of the US dollar, in order to hedge against future exchange rate volatility, which in turn continues to prop up the US dollar in global currency markets. Demand for US government debt, which is denominated in dollars, works in a similar way; high global demand for Treasuries motivates purchases of those assets, which pushes up the price of US government bonds relative to other global assets, and pushes down interest rates (a dynamic I’m happy to go into in a future newsletter). Early in the pandemic, global fears about access to US dollars for those obligations motivated a large selloff of US government bonds, which sent a panic through global asset markets, and pushed the Federal Reserve, under Jerome Powell’s leadership, to reinstate dollar swap lines, or an agreement to accept local currency denominated assets as collateral for their US dollar value, for fourteen monetary authorities.1 The Fed also created a repo facility that allowed central banks that did not qualify for dollar swap lines to sell their US bond holdings to the Fed with a commitment to repurchase them in the future, to increase international access to US dollars in an uncertain economic moment. These programs were phenomenally successful insofar as they stabilized global asset markets and halted the selloff of US Treasuries; they also increased the volume of US dollars held as reserve currency around the world.

In my time as a graduate student, and also more recently, there have been numerous debates about whether the US dollar would lose its dominant position among international currencies. The most recent flareup of this debate occurred soon after the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, and the US’s decision to block key Russian banks from the SWIFT (Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications) system, the network that enables payments between international banks. The decision to remove those key Russian (and Belarusian) banks from SWIFT halted payments (and specifically dollar transfers) to and from Russia, effectively locking Russian economic actors out of lots of global business, and hindering its ability to make other payments denominated in US dollars. In response to this, global demand for the US dollar decreased, particularly among the middle-income bloc of countries sometimes referred to as the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa), as trade partners with Russia shifted toward holding renminbi and rubles. There was a decrease in the usage of the US dollar for international transactions soon after the decision to lock Russian banks out of SWIFT, and also a decrease in international holdings of US Treasuries. However, attempts to counter the dominance of the US dollar by building up a basket of currencies and a payment network using the renminbi as a counter reserve currency have either failed or been slow to scale upward.

How could current monetary policies affect dollar dominance? First, the US dollar has depreciated since the second inauguration of Trump. This tends to happen in the aftermath of tariff hikes, and there have been many of them since January 2025. There was also plenty of dollar exchange rate volatility during the first Trump administration, after the various trade wars initiated back in 2018. Dollar depreciation could chip away at dollar dominance, if monetary authorities around the world move, en masse, away from the US dollar as a reserve currency. However, volatile currency movements aren’t the only factor motivating holdings of different currencies as reserve currencies. Miran’s stated desire to decrease US interest rates could also help, since lowering interest rates can contribute to depreciation trends, all else equal, but it still wouldn’t be enough to rapidly reverse global opinion about holding the US dollar as reserve currency.2 If global institutions shifted as a group toward denominating international obligations in currencies other than the US dollar, that would, by contrast, help the dollar lose ground as the dominant global currency.

More next week on the accusations of dedollarization, why they have generally been premature, and what could be changing in the midst of all this administration’s policies (my eyes are on the looming government shutdown, as of Tuesday, September 30, 2025, anyway). I’m staying tuned, one way or another!

This group included the Bank of Mexico, the Bank of Canada, the Bank of Brazil, the ECB, the Bank of England, the Switzerland, Sweden, Norway and Denmark’s central banks, Singapore’s monetary authority, the Bank of Japan, the Bank of South Korea, and the Federal Reserves of Australia and New Zealand.

The quick and dirty explanation for this is that if a central bank lowers interest rates, deposits in that economy are less profitable, encouraging international investors to liquidity their domestic deposits in that country’s currency, and to move those deposits elsewhere in the world with greater returns. In practice, this is time consuming and hardly cost free.